freedom of speech in the shape of storytelling changes lives

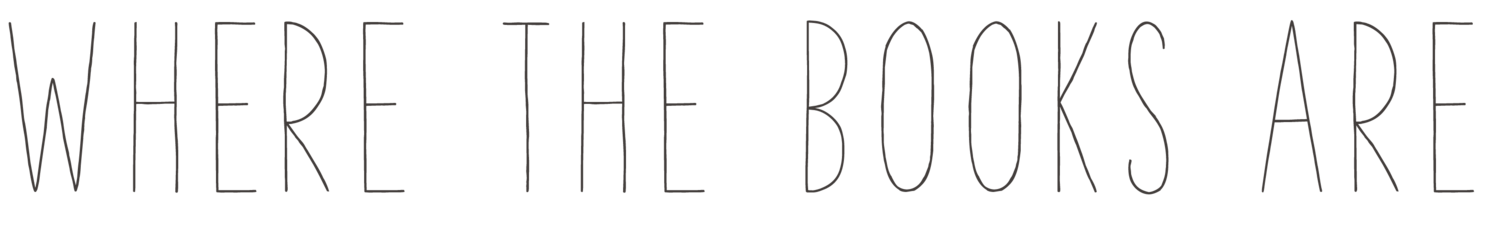

/THE STAMP COLLECTOR

by Jennifer Lanthier, illustrated by Francois Thisdale – Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2016

ages 6 years to adult / language, powerful lives

Preserving stories hinges upon valuing stories and, in a circular way, valuing stories hinges upon hearing the stories that have been preserved.

There have been many defiant instances of bravery where books and stories have been saved at great peril, and all of these required some noble soul who had first developed an appreciation—an awe even—for stories.

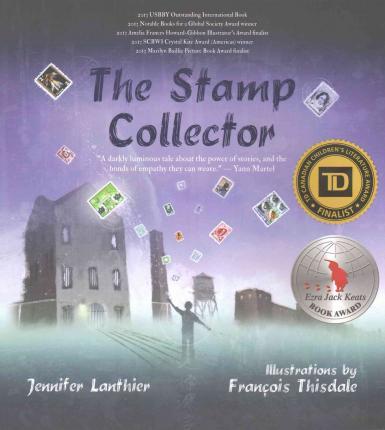

In contrast stand the many instances of book burning and suppression of writing ignited by corruption, power and fear. In his book Books on Fire, Lucien X Polastron wrote about the destruction of libraries (both private and public), saying:

“Why? Because, as the lawmakers of ancient China and the Nazis in Czechoslovakia decided, an educated people cannot be governed; … because the nature of a great collection of books is a threat to the new power …

But there is yet another, more deeply buried, meaning that is always present beneath all others: The book is the double of the man, and burning it is the equivalent of killing him.”

(emphases are ours)

The Stamp Collector is an imagined story that speaks to both of those responses:

It tells the story of two little boys who grow to manhood. One: a writer and a dreamer. The other: a dreamer of a different sort who, impoverished in both body and soul, becomes the writer’s prison guard.

In a time when “grey men say words are dangerous” and both men are trapped by economic necessity because “Dreams do not buy bread. …Stories do not buy bread” their lives cross.

Even while imprisoned, the writer touches lives. The story he tells has many admirers and they write letters to him in jail. The guard does his duty and “places the letter in a file to be forgotten.” But first, the guard removes the stamp to add to his collection of stamps that are not rare or precious but beautiful.

In the passage of time and after a troubling dream, the guard begins to read some of the letters. He bravely starts to share the stamps with the writer. It is enough for the writer to know he has not been forgotten.

Eventually, as the writer withers, the guard brings the letters to him as well. And the writer tells the guard the story that will be his last. “And the story fills the guard’s soul until he wonders if he will burst.”

Finally, the writer dies and the guard knows what he must do: at enormous personal risk he travels to a library and begins to write the story he has been told.

This is a touching and troubling book. It is precisely written, allowing the reader to step into the shoes of the writer and the guard alternately. And in doing so, it allows us to consider our own course in life and our own willingness to take risks, defend truth and art, and sacrifice for others.

Reasons to love this book:

Living in a time and place where freedom, and especially freedom of expression, is protected, it is easy to take all of that for granted. This book helps to remind readers that those freedoms are rare and to be cherished.

By including the evolving stories of both men, it becomes clear that there is always room for personal growth and change.

The very concept of freedom becomes hazy as we recognise that it is not only the writer whose freedom is curtailed—the guard has limited freedom too. And then we start to wonder who has the greater freedom: the writer who can think, dream and create even within the walls of a cell, or the guard who can wander freely from the prison but can’t escape the poverty or the bleakness of his life.

The setting for the story is clearly Asian, but nowhere is there mention of a specific country or regime, allowing for the same story to be played out around the world. There's an author’s note at the end of the book that is really worth reading. It talks about writers who have been imprisoned and the catalysts to their release, and ends on a personal note about the connection between the author and a writer who remains in prison.

The artwork is at once inspiring and gut wrenching. It perfectly captures the severity of prison life and the desperation of both men without being gruesome or graphic, making the story appropriate for younger children.

A small reading hint:

This is not a short book—you’ll need a bit of time to both read the story and to discuss it afterwards. In many ways it reads like a poem, and deserves a serious and expressive tone.

The stamp is a key to another world—one that's new and full of adventure. And stories!

It’s true as Polastron wrote, that “the book is the double of the man’ but it’s also true that the man is the double of the book—the stories we read shape so very much of whom we are. We know instinctively the power of stories and this wonderful book reminds us that stories change lives and telling and hearing stories is a basic human right. It inspires us to be on our guard for infringements of that right.

A portion of the book's proceeds are donated to PEN Canada which helps to support the Writers in Prison letter-writing campaign.